It comes up a lot when I work as a literacy consultant on elementary and middle school campuses.

Teachers are concerned that their students don’t have sufficient background knowledge to comprehend in deep and meaningful ways. It’s true. What concerns me is that sometimes it feels as if the conversation ends there; that somehow just in the saying it aloud we’re done.

No need for more discussion. No collaborating to find other options. No way for our kids to overcome that obstacle.

But there is more to discuss, more collaborating to be done and plenty of ways for our kids to blow that obstacle to smithereens.

Before I get to masterful ways I’ve observed teachers deal with the background knowledge issue, I want to share an anecdote that I know will help to clarify how background knowledge is not the big, foreboding problem that it sometimes appears to be.

Last week I was in a rural district in North Dakota. I’ve been visiting this school district for over a year now and this particular visit was to focus on instruction in Tier 2 and Tier 3 intervention sessions on the elementary and secondary campus.

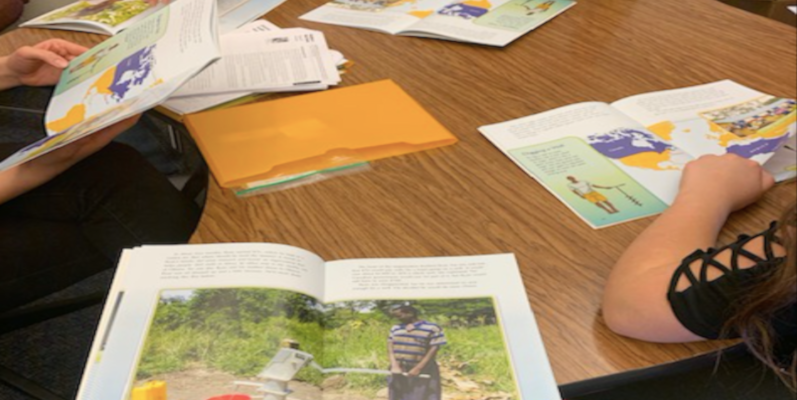

One session in particular fascinated me as I listened in while sixth grade students read a few pages from a book about Ryan Hreljac. I won’t go into his story because you can read more about this remarkable young man from the link provided here.

The kids read a few pages and then the interventionist, the brilliant Ms. P, asked them to stop so that they could talk about what they’d read.

Ms. P: “What information were you able to get in the sidebar here on this page?”

Student: “This says that digging a water well is made much easier by the use of an auger. And that it’s inexpensive and simple for people in a village to get cleaner water by digging a well. Ryan’s organization helps to provide the tools and information through their donations.”

Ms. P: “Was the sidebar helpful to you as the reader? Did it help you to know what an auger is?”

Student One: “It was helpful, I guess, but I already know what an auger is. We use one on our farm to dig holes for corner posts.”

Student Two: “Dad and I always use one of those when we go ice fishing. I think dad thought I wouldn’t be strong enough to use one just because I’m a girl, but he was wrong. I got auger skills.”

Student Three: “We’ve been told my whole life to stay back from the auger when dad is harvesting. It’s dangerous when the threshed grain from the grain pans of the combine are moved up and into the grain holding tank.”

I was astounded that three out of the five kids sitting at the table had more than sufficient background knowledge for the vocabulary word the teacher thought she might need to clarify. I couldn’t help but think of suburban Texas kids I work with often as a consultant. They most likely would not have been able to contribute as much as these kids in rural North Dakota had when it came to the word “auger”.

Let’s examine that scenario closer. Ms. P, like all great teachers knew that if her band of readers was to understand the short book on Ryan Hreljac and his non-profit organization’s work, they’d need to know the highlighted word on that page. Understanding the meaning of the word and its significance to the simplicity of Ryan’s clean water support for villages on the continent of Africa was key.

In this instance, though, Ms. P needed only to activate their knowledge. She had only to ask that simple question, “What information were you able to get from the sidebar on this page?” Had her students looked back at her with confusion, she would have needed to build background knowledge.

I hate to boil this done to uber-simple terms, but that’s really all that’s needed when it comes to background knowledge. As teachers we simply have to plan for activating and/or building prior knowledge for our students.

The other good news is that it doesn’t require a whole lot of prep on the teacher’s part.

If Ms. P had found instead that her kids were clueless about the word auger, she could have simply defined it (in kid-friendly terms) and then showed a short youtube video of an auger in action. All that was needed were a few short minutes building background knowledge so that the kids in her group could come to understand the process of digging a well in those few pages of the book about Ryan Hreljac.

So back to the ways in which we can stop fretting that our students don’t have sufficient background knowledge to comprehend the short text they have to read or to perform well on an end of unit assessment. When we read with our students or assign a selection, we can first activate their background through a simple question, “What do you already know about _________?” If we discover they have insufficient prior knowledge, we quickly (taking only a few minutes) build their knowledge through a short demonstration, example, media resource, picture or diagram.

I want to leave the reader with an article by Fischer, Frye, and Lapp that has extensive information on this subject of background knowledge. The article defines and provides examples of various ways to teach students how to activate and build their own background knowledge which is what we, as teachers, aspire to facilitate for every student.

To function successfully in a 21st century environment filled with new media texts and topics, one must be smart about one’s own base of knowledge and how to support one’s own intellectual growth. Because we can be sure to offer students the experiences they need if, in addition to teaching them content, we also show them how to teach themselves.

Fisher, Frye, Lapp (2012)