My last year of high school I graduated early in February so I could join my parents in Great Britain. The freedom I experienced as an eighteen year old traveling around England after dad’s job took our family there for two years changed me. Even now, many decades later, I still find that I am a bona fide Anglophile.

That’s how I explain my recent obsession with Penelope Keith’s Hidden Villages series on PBS. Don’t even ask me how many times I’ve watched each episode. It’s embarrassing.

In one episode, filmed in Cornwall, Keith introduces viewers to the Minack Theatre. I’ll not go into detail here, but I paused the episode and immediately began to read all I could about Rowena Cade. Ms. Cade, her gardener and another chap single-handedly (over a period of about 5 decades) built the theatre that sits atop a jutting cliff above the sea. It’s a fascinating story—one I’ll hope you’ll investigate on your own.

Is there a way that we can foster that kind of ardent inquiry in our young students?

I believe we can.

And the language arts curriculum is the perfect venue.

Teachers and coaches should carve out time for collaborating to choose texts that prompt curiosity, wonder and a disposition of inquiry. It’s critical for teachers to be committed to the path of inquiry that presents itself based on the questioning of students. We can support and facilitate an environment of wonder and honest, innocent questioning, but we have to be careful of forcing an agenda or pressing our own preferences.

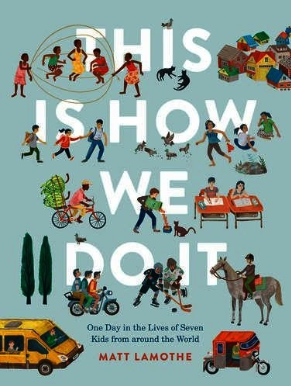

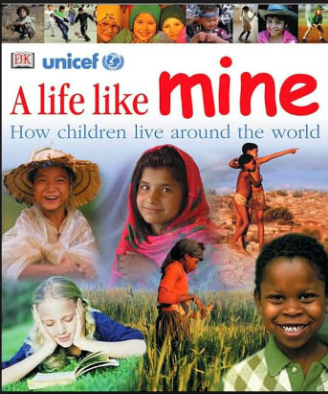

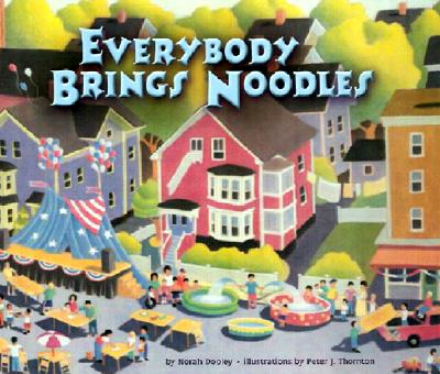

Books, high-quality texts, are the catalyst for inquiry. Questions about how other kids live in places around the world are best explored through books like This How We Do It: One Day in the Lives of Seven Kids from Around the World by Matt Lamothe, A Life Like Mine by DK Children’s Books, Everybody Brings Noodles by Norah Dooley.

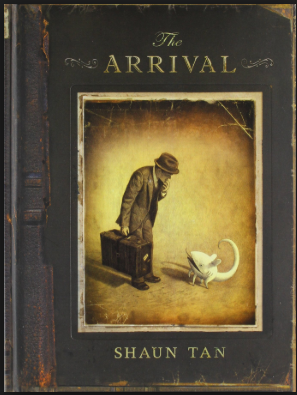

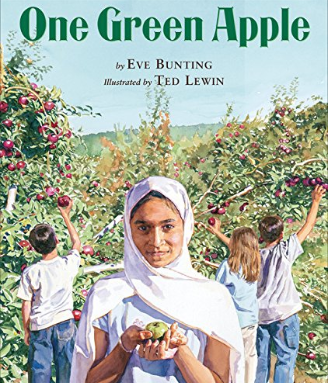

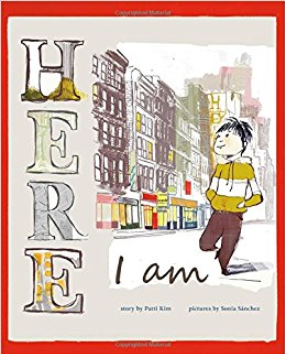

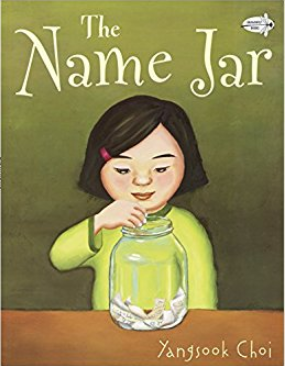

Stories of immigration are stunningly portrayed in Shaun Tan’s The Arrival, Eve Bunting’s One Green Apple, Here I Am by Kim and Sanchez, The Name Jar by Yangsook Choi. Books about our natural environment by Seymour Simon, Melissa Stewart and Jess Keating leave kids begging for more information about the topics these brilliant authors present.

Are you willing to reflect at length about the inquiry-life in your own classroom? Do you see quality unbiased texts as mentors leading to a disposition of inquiry for your students and yourself? How frequently do you engage in conversations with peers about books that lead to conceptual inquiry for your students? Are you someone who has developed a disposition of inquiry in your own reading life?

Whether or not you are currently creating an environment of wonder, curiosity or deep understanding through the books you read aloud and provide in your classroom library, the simple act of immersing students in compelling text is evidence of an inquiry stance. Actively pursuing students’ questions, honestly thinking aloud yourself, explicitly calling attention to the way in which readers’ thinking changes as they read—all of these habits are an authentic pedagogy of inquiry and work to make the integration of content in the reading workshop a natural experience.

Discussions abound about ways to motivate reluctant readers. “How can I motive my kids who say they don’t like to read?” I think we’re asking the wrong question.

The question should be, “Am I exposing kids to texts that make it difficult for them not to engage and then find pleasure in exploring on their own?”

It’s on us.

When we thoughtfully and intentionally read aloud compelling, provocative texts (and fill our shelves with those same books), we create a community where inquiry is the norm and not the exception. Page upon page from great texts do the work for us.

And our young readers are never the same.