As an educator, I enjoy reading articles written primarily for people in the corporate world. Harvard Business Online had an interesting piece about making the most of unique experiences in an effort to build one’s own identity capital. The article began with how to build identity capital and in particular how Meg Jay, author of The Defining Decade, elaborated in her book on the original work of James Côté.

Expanding on the work of sociologist James Côté, clinical psychologist Meg Jay defined the concept of identity capital in her book, The Defining Decade, as an individual’s collection of personal assets, or how we “build ourselves—bit by bit, over time” through experiences. (Solberg, 2019)

I couldn’t stop thinking about that particular excerpt from the article. It made perfect sense for me to transfer that idea to the world I know well–education.

Our adult kids are married and have children. The two youngest grandchildren are boys and would have attended prekindergarten this year. Due to COVID, the boys were not going to attend for safety reasons. My consulting business allows me several days a week that are free to teach the boys in our home and our adult kids and their spouses agreed it would be best.

I knew it would be a learning experience for me as well as the boys. Every day we’re together, I learn about them as learners, about me as a partner in their learning, and about the practice of supporting emerging readers.

Over the thirty-plus years I’ve been in education, I’ve observed and supported readers of all shapes and sizes from PreK through the 8th grade. Throughout those years, I’ve read professional books, journal articles, and research publications in an effort to stay up-to-date. All that reading was enlightening, but I think the observation of real kids in real time learning to read has been my greatest teacher.

I knew that in our PreK academy we needed lots of reading in a variety of modes and literacy events throughout each day. Shared reading, thoughtfully chosen read-alouds, independent reading (appropriate for emerging readers), letter-sound exploration and writing would all work to support the lads.

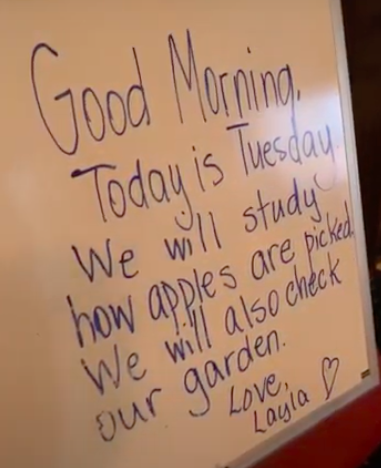

We start every day with a morning message and then explore the text for letters, letter combinations, punctuation, and the like. We read poems and song lyrics, pore over recipes and directions to games or activities. (The boys and I had to study the directions for putting together a zig-zag riding toy. I wish we’d recorded it. They “read” the directions and I wielded the tools.) We read environmental print and had a scavenger hunt throughout the house so they could search for the names of all their family members. All this and more in an effort to immerse them in words, sentences, and texts so they can “break the code”.

So why start this blog post with the article on identity capital?

All my years observing and supporting readers, learning from them and their experiences, has taught me that there are two pillars that support the mighty structure of learning to read; skills and identity.

Every reader must obtain the skills for decoding and comprehending. They must also develop an identity as a reader. One without the other, I’ve observed, makes for a fragile reader. Lauren Meier, in the Journal of Teacher Research posits:

Being a reader in the fullest sense means reading voluntarily, having confidence, collecting books, recommending books to others, talking about reading, knowing different authors and illustrators styles, reflecting on reading, making connections and thinking critically (Fountas & Pinnell, 2001). So how do we as teachers help to foster a student’s love of reading, and give them the opportunity to have a positive reader’s identity? “It should be the teacher’s aim to give every student a love of reading, a hunger for it that will stay with him or her through all the years of his or her life” (Layne, 2009, p. 6).

On the first day of our PreK year, I asked the boys to share with me what they hoped they learned in our year together. Owen (age 4) jumped to his feet and said, “First I have to tell you something sad. I don’t know how to read. I’m sorry.” Jack (age 5) also spoke up, “I don’t know how to read either. Shepherd and Asher (Jack’s older brothers) can read, but I can’t read.”

I assured them that we would work together to listen to great books, talk about books, learn letter sounds and even write our own books this year. They didn’t look convinced, but I’m confident in their ability to grow their identity capital and I’m committed to facilitating an environment in which that can happen.

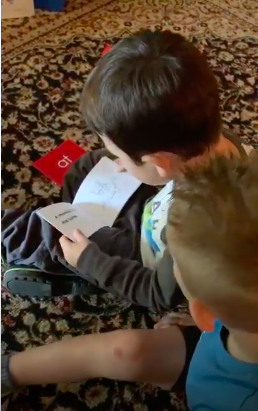

That identity capital had to be nurtured on our first day. For years I’ve used The Short Books for all the early readers in my learning community. Individually, I sat with each lad and introduced the first sight readers in the series. When Jack read the first two pages he giggled timidly. He repeated the same little laugh after each page. I asked him in the end, “Did you think that book was funny?”. “No, I was happy because now I’m a reader.”

And that’s precisely why I have made good use of those sight reader sets again and again. Kids can immediately use the new learning of sight words along with simple sentences and heavy picture support to read. They believe in the first few pages, certainly after the first few books, that they are readers.

I don’t have to make the boys wait until they’ve learned all their letter sounds or can read the first 100 sight words in order for them to believe they are readers. Our work of learning to read is fluid and flexible. We learn together to recite silly poems and read the directions for planting radish seeds in our fall garden. We view celebrities reading books online and we listen intently to our audiobooks that we love. We play with words and make letters by tracing in sand. We sit together in the library center poring over the new books added each week. They “read” the pictures or retell the story as they remember it from a recent read-aloud.

All these things work together to build the skills necessary for decoding and reading fluently. I must also pay equal time and attention to fostering their identity capital.

Every day I watch as they enjoy their “individual collection of personal assets, how they build themselves–bit by bit, over time through their experiences.”

“How To Make The Most Of Unique Job Experiences | HBS Online”. 2020. Business Insights – Blog. https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/unique-jobs.

Meier, L., (2015), “Choice and the Reader’s Identity”, Journal of Teacher Action Research, Volume 1, (Issue 2, Fall 2015), Pg. 21.