One of the things I’ve learned over the years when talking with teachers about students and comprehension instruction is that sometimes as proficient readers ourselves we don’t fully understand where to begin when working with our young readers. When you are a master at any given skill it’s sometimes difficult to identify the “first step”.

As teachers we’re constantly observing students, the problems they encounter and then working to analyze what we need to do to support them toward mastery. So many times we design instruction that we believe starts at step one (in the proficient reader’s mind) only to realize later that our “step one” was really step twelve (for the emerging reader).

For example, proficient readers understand that it’s critical to monitor their own comprehension as they read. We set out then to teach our apprentice readers that they should monitor their understanding. That to us, as proficient readers, is step one.

Not for the rookie reader, however.

The Problem

What does it mean to monitor? What are the specific reading/thinking moves that a young reader engages in when monitoring their comprehension?

My step one is not a novice reader’s step one. As a teacher, I have to break down the individual bits of the process of monitoring because what I actually do as a proficient reader is:

- Pay attention to when I understand and when I don’t understand

- Determine where the confusion began for me in the text

- Assign a strategy from my repertoire of strategies to make meaning

- Employ the strategy and work to arrive at deep meaning

All of this takes a tremendous amount of persistence on the reader’s part. We know our kids have strategies for making meaning because we’re modeling, guiding and providing ample time to practice. What I don’t see consistently when I work with young readers is the ability or commitment to persevere in this process of monitoring and fixing up.

The Solution

Recently, in a third grade classroom I saw this very issue. The students knew the strategies and could call them by name; they possessed declarative knowledge. They could tell you the steps in carrying out the strategy. It was clear they had control of procedural knowledge. But what they did not show us, on a consistent basis, was their ability to know when or why to employ the appropriate strategy on their own (and stick with it). This is the most powerful type of knowledge in comprehension known as conditional knowledge. I wrote about this trio of knowledge types in part three of a series on strategy transfer here.

The teacher and I discussed that we should begin with a lesson that would lead the students in knowing when and why to apply the appropriate tools they already had in their collection of known strategies.

But, the question remained—was that really step one for these readers?

We determined that before we could address anything else we had to confront an altogether different problem. The students know the strategies, they know the steps needed to apply the strategies, they were becoming pretty adept at matching a particular strategy to the breakdown BUT we were not seeing their ability to stay with the process until deep meaning was made.

So…how to teach persistence to make meaning when comprehension breaks down?

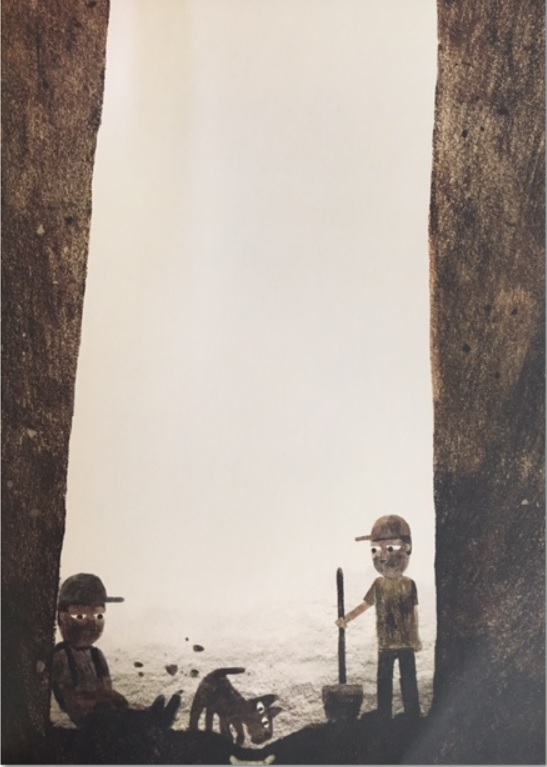

Well, thanks to Mac Barnett and Jon Klassen, we had the perfect resource—Sam and Dave Dig a Hole. The teacher allowed me to read and facilitate a discussion on how they, as third grade readers, could apply ideas from Sam and Dave in order to persevere in the face of meaning meltdown.

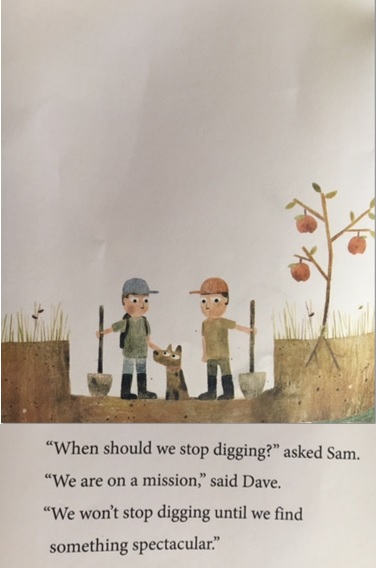

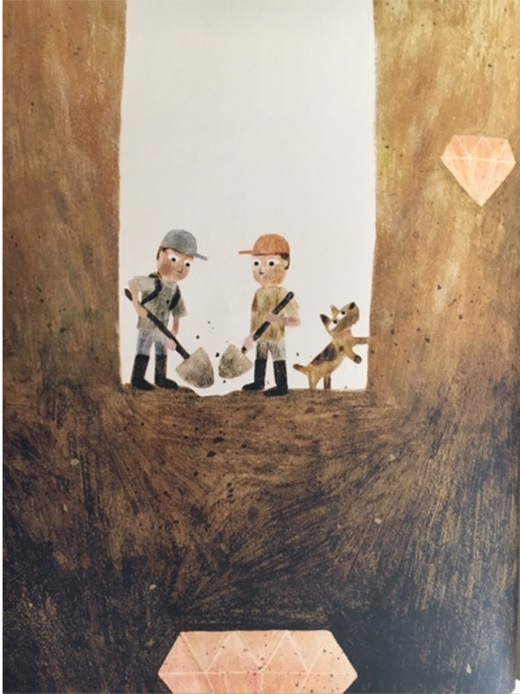

Sam and Dave start out their digging adventure by proclaiming that they’ll dig until they find “something spectacular.” They dig for a while and become discouraged so they head off in a different direction. This is repeated throughout the story, but their persistent pup continues to dig until finally the boys are exhausted, fall asleep and the dog in the story ends up with his own treat.

The discussion following the read-aloud was full of insightful comments by the kids. I asked a few questions hoping to help them relate their understanding of the story to ways in which readers behave when they encounter a text. One student caught on immediately and said, “Even when it’s hard, readers should ‘keep on digging until they find something spectacular’!”

At that point, the teacher and I could move forward in subsequent minilessons teaching and modeling the additional steps inherent in a reader’s ability to apply conditional knowledge. The task of asking when and why to employ a strategy while reading is an arduous task and we hoped to give students an unforgettable learning experience they could rely on and come back to in their comprehension work moving forward.

Step One: possessing a head and a heart understanding of the reader’s commitment to persevere until the “something spectacular” of making deep meaning is accomplished.

There were some pretty remarkable and unintended effects of allowing Sam and Dave to mentor our students in persevering. Less than a week after that mini-lesson, our district administered a four-hour benchmark reading test to all 3rd-6th grade students. I was assigned to the group of students who are allowed an opportunity to take the test in a small group setting. Of the six students in the room, four had been with me on the day we read Sam and Dave Dig a Hole.

As a part of their testing accommodations, I was allowed to read the questions and the answer choices. When the first student raised her hand to signal she was ready, I read as I was allowed. She looked up at me and said, “Mrs. Kimmel, this is where I go back to the story and dig deep until I find something spectacular, right?”

Step One. The apprentice reader’s step one.

Not step one for me as a seasoned, proficient reader.

It takes a lot of time to analyze our student’s struggles and match instruction to their specific needs, but it is absolutely worth it.