When our daughter, Paige, was five she fell while standing on a chair. She hit her head and was unconscious for what I’m sure was only a few minutes, but to this newb parent it felt like an eternity.

We were living in Austria at the time and our pediatrician had practiced in America for almost a decade before returning home. He spoke excellent English (one of 5 languages he spoke fluently). But on this particular day we had a little language snafu.

Dr. Pollock began, “I’ll give you directions to follow over the next few days. It will be important for you to watch her closely and limit her physical activity. As you can see she is having a convulsion.” The “c” word threw my husband and I into joint panic mode.

I said rather forcefully that I thought he should do something. Dr. Pollock assured me that Paige would be fine. “If she’s having a convulsion right now, shouldn’t we be doing something?” I asked. The doctor laughed and said, “Oh, I sometimes get those words confused. I’m sorry. What I meant to say is that she is having a concussion.”

Uh, yeah. A concussion is not a convulsion.

And at the time, it was not funny.

Part Three in the series, Teaching Young Readers is Not for the Fainthearted is an attempt on my part to clear up some confusion. There are so many terms about reading. Let’s be clear. It doesn’t matter how many years have elapsed since your university studies in education. Maybe it’s one. Maybe it’s twenty-one.

Teaching young children to read requires that we intimately know the terms, how to plan for quality instruction and additional supports needed to facilitate optimal growing conditions for all our “reading seedlings”.

When, as professionals, we are talking to one another (or worse yet, about a student with a parent/guardian) about the finer points of teaching reading and terms are used incorrectly, that’s not funny either.

Do not confuse phonics and phonemic awareness as being the same thing. Because they aren’t. If there is confusion, I’m concerned that the reading instruction for students might be a little wonky and that’s not helpful for growing readers.

Just as I hold my doctor, lawyer, accountant, financial adviser, pilot, (or anyone else in my life who offers a service that has some level of risk attached), accountable to know everything there is to know about their field, teachers are accountable in the same way to know their stuff.

We are practitioners. I’ll say it again–we need to know our stuff. And if, for some reason, we’ve forgotten or we’re confused, we need to get clarification and/or support.

#rantover

What It Is

- Alphabetic Principle: The concept that letters and letter combinations represent individual phonemes in written words

- Phoneme: The smallest unit of sound within our language system. A phoneme combines with other phonemes to make words. Phoneme Isolation: Recognizing individual sounds in a word (e.g., /p/ is the first sound in pan).

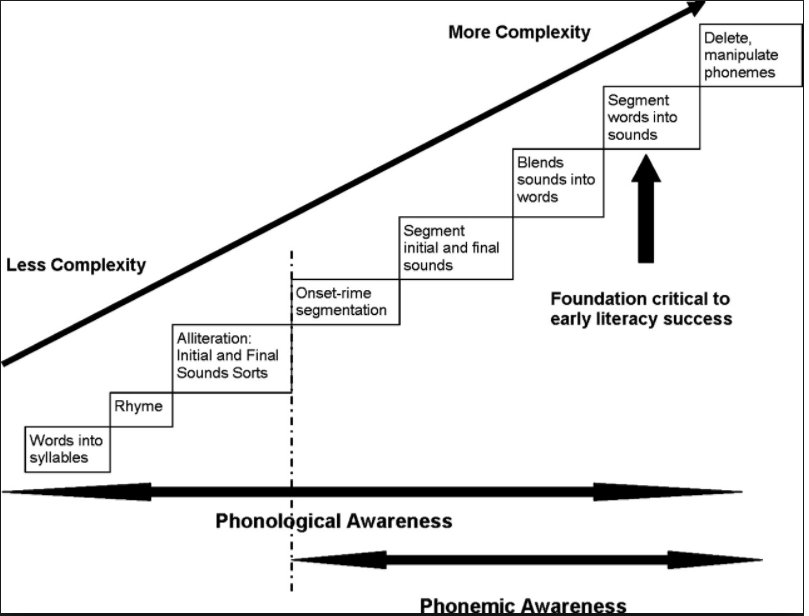

- Phonemic Awareness: The ability to notice, think about, or manipulate the individual phonemes (sounds) in words. It is the ability to understand that sounds in spoken language work together to make words. This term is used to refer to the highest level of phonological awareness: awareness of individual phonemes in words.

- Phonics: The study of the relationships between letters and the sounds they represent; also used to describe reading instruction that teaches sound-symbol correspondences.

- Phonological Awareness: One’s sensitivity to, or explicit awareness of, the phonological structure of words in one’s language. This is an “umbrella” term that is used to refer to a student’s sensitivity to any aspect of phonological structure in language. It encompasses awareness of individual words in sentences, syllables, and onset-rime segments, as well as awareness of individual phonemes.

These are some, not all, of the important reading terms that every teacher of reading should know and understand. For a list with additional reading terms, taken from the FCRR site, click on the image below for a two page glossary I created for this post. For a more comprehensive list of reading terms found at FCRR, Florida Center of Reading Research, click here.

What Must Be Done and How to Do It

Instruction and practice in phonemic awareness:

Many researchers suggest that the logical translation of the research to practice is for teachers of young children to provide an environment that encourages play with spoken language as part of the broader literacy program. Nursery rhymes, riddles, songs, poems, and read-aloud books that manipulate sounds may be used purposefully to draw young learners’ attention to the sounds of spoken language. Guessing games and riddles in which sounds are manipulated may help children become more sensitive to the sound structure of their language. Many activities already used by preschool and primary-grade teachers can be drawn from and will become particularly effective if teachers bring to them an understanding about the role these activities can play in stimulating phonemic awareness. (International Literacy Association)

There is a hierachy of phonemic and phonological awareness skills. Notice the chart above makes clear the distinction between phonological awareness and phonemic awareness.

Instruction and practice in phonics:

Although there are many different types of or approaches to phonics instruction (e.g., intensive, explicit, synthetic, analytic, embedded), all phonics instruction focuses the learner’s attention on the relationships between sounds and symbols as an important strategy for word recognition. Teaching phonics, like all teaching, involves making decisions about what is best for children. Rather than engage in debates about whether phonics should or should not be taught, effective teachers of reading and writing ask when, how, how much, and under what circumstances phonics should be taught. Programs that constrain teachers from using their professional judgment in making instructional decisions about what is best in phonics instruction for students simply get in the way of good teaching practices. (International Literacy Association)

A word about the how. (Two thoughts actually about the how of instructing young readers in phonics and phonemic awareness.)

Teaching reading and writing as reciprocal processes is a powerful tool for supporting struggling learners. Furthermore, making explicit connections to searching, monitoring, and self-correcting exponentially increases children’s opportunities to develop parallel processes for reading and writing. As teachers explore this reciprocal relationship in the classroom, they will be surprised at how children learn more quickly as they begin to make connections (Clay, 2001; DeFord, Lyons, & Pinnell, 1991)

Reading and writing must be taught as though they are partners joined at the hip.

When writers write, in order to create meaning, they must inevitably encode, or use individual known sounds to create words. When readers read, in order to make meaning, they must decode or translate printed symbols in words to sounds and those sounds into a complete word. As children write and encode (spell), we’re able to see the phonemes they “own” because we observe them being used in the young writer’s message to create meaning.

In their book, Teaching Phonics in Context, David Hornsby and Lorraine Wilson posit:

Although there is a need for the explicit teaching of phonics:

- the reading and writing of connected text takes priority;

- the teaching and learning of phonics is always contained within, and subordinate to, genuine literacy events; and

- children spend much more time reading and writing (in which they learn to apply their phonic knowledge) than they do in the actual study of sound-letter relationships.

Phonemic awareness and phonics must be taught and practiced in context. Teachers who commit to a balance of reading aloud, shared reading experiences, guided reading instruction, independent reading by all children with thoughtful connections to phonics and phonemic awareness serve students well in learning to read.

I am fully aware of how difficult it is to teach readers to read proficiently. I’ve been working at the work for almost three decades now. Believe me when I say that I’m as hard on myself as I am on others (maybe harder).

Teaching children to read is a prodigious privilege and a weighty responsibility. Let’s do everything in our power to stay informed by reading and learning all we can about growing proficient readers. Let’s also be incredibly discerning about what we read. Choose reliable, knowledgeable experts in the field to follow.

Let’s know our stuff when it comes to reading instruction. We owe that much to our readers.

The information in this blog can’t be shared enough. There is so many misconceptions out there about the science and art of teaching reading and writing.

Terry,

Thank you for your comment. It’s the most important work we do in education.