In the three previous posts on strategy transfer (here, here and here), we looked at the elements of creating a system whereby students engage in the powerful work of moving from single use of a teacher-coached strategy to the independent, autonomous use of the most effective strategies chosen from a repertoire at the appropriate time to aid in comprehension of challenging texts.

This post will provide information on student goal setting as an essential element of a system that facilitates strategy transfer.

We are constantly having discussions in our building about the best way to meet the needs of our students who are not meeting grade level requirements for reading. Some teachers feel the best way to meet the needs of these students is exclusively through small group instruction. Others are concerned that if these students are only receiving remediated instruction, they’ll fall further behind since they are not also receiving instruction in the current grade level standards.

I admit that I fall in the “both/and” camp. Students need instruction in both grade level standards AND instruction in the components of reading that they need to be able to read at grade level proficiency. When students receive only remediated instruction they run the risk of falling further behind as they miss out on instruction and practice in current grade level standards. It’s hard to create time for on-level instruction and remediated instruction for our students, but it is critical.

When thinking about setting goals for students in reading, both types of instruction should be considered as a basis for the goal setting. If a student is reading at grade level, then the current standards provide criteria for student goal setting.

For example, a fourth grade teacher launching a unit that will lead readers to listen to, view, and read informational texts about traditions cultures use to relate stories and pass down information will set goals that are in alignment with these standards. All students in the class will set realistic, relevant personal reading goals and both teacher and students will monitor the progress of those goals.

In addition, students requiring additional support in reading will work on specific goals that move them toward mastery of on-level skills. For the purpose of discussion in this post, I’ll focus on setting goals for students who require additional support.

How do you guide students in setting goals? Once again, I’d like to suggest The Reading Strategies Book by Jennifer Serravallo as a resource. Jennifer states in the introduction:

Once you’ve decided, based on formative assessments, what goal the student is to work on, I recommend having a “goal-setting” conference to discuss this with the student. If at all possible, you may even put the assessment on the table in front of the student and ask the student to reflect on what he or she notices from the assessment. Sometimes a student will know what he or she needs to work on, and when the goal can come from the student, the student will be all the more motivated to work on it (Pink 2009).

During independent reading, students need a visible reminder of the goals they’ve set for themselves. There are a variety of ways that can be done. The reminder needs to be appropriate for the age and developmental stage of the student. (Example below from The Reading Strategies Book by Jennifer Serravallo).

A student copy of the goal/action steps is especially helpful when conferencing with students as the goal is the basis for the conversation and the ongoing assessment for that student. Not only can the teacher monitor a student’s progress toward their goal, but this practice allows the student to self-assess. Self-assessment has the added benefit of promoting student achievement and motivation.

This summer I read Who’s Doing the Work? How to Say Less So Readers Can Do More by Burkins and Yaris. The authors posit that one of the reasons students are struggling to read independently is due to the fact that teachers work hard to put scaffolds in place to support students.

So much support has been provided, however, that students aren’t given opportunities to regulate their own strategy use. Burkins and Yaris share that “new generation” literacy practices equip students with strategies and instead of prompting them specifically with “Draw a plot diagram so you can keep up with the elements in this story”, teachers can simply ask, “What strategies can you choose from to keep track of your thinking as you read?”.

This practice of modeling multiple strategies for students to tuck away in an ever growing repertoire moves students toward self-regulated strategy use. Students are put in a position of setting a specific goal, learning a variety of strategies (at least three to four) and then being held accountable to use those strategies when they read difficult or inconsiderate texts.

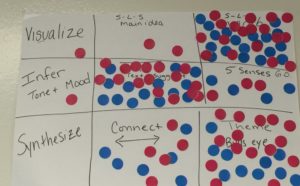

I’ll end this post by sharing a classroom practice I observed in Aubrey Steinbrink’s class last year. As I shared in a previous post, Aubrey designed a close reading protocol for students to use during their independent reading time. During the closure portion of the lesson, Aubrey brought students back to the meeting area on the floor of her classroom and debriefed with students regarding their strategy use.

After restating the lesson objective Aubrey gave several minutes for students to share the strategy they had used that day (choosing from their repertoire) that had been most effective for them as readers. She used a variety of ways for them to share throughout the year, but this day in particular, a consensogram was used. Aubrey included in the chart the handful of strategies students had been learning and practicing over the last couple of weeks. Students then put a dot in the column indicating the strategy they’d used during independent reading. It was an effective visual showing the number of students that had tried specific strategies.

That wasn’t the most powerful moment during this lesson closure, though. Aubrey then asked the students to talk about why they’d chosen that strategy and when they might use it again. Sound familiar? It should. This was intentional so that kids had practice in applying and talking about conditional knowledge.

It was amazing to see students share about their strategy use and to observe other kids listening intently. Aubrey asked for additional comments to close out the discussion and some kids shared that next time they were tasked with inferring tone and mood, they were going to try a strategy they’d heard their classmates promote.

Coaching students through a systematic process to set goals to improve reading, then trying out a handful of strategies as steps to accomplish that goal is a powerful plan for improvement.

In the final blog post in this series I’ll write about the incredible return (John Hattie’s research shows a 0.75 effect size) on effective feedback as the final element in the powerful work toward facilitating strategy transfer for our students.