It’s one of the most challenging strategies for students to understand, and one of the most problematic strategies for teachers to instruct. Summarizing has to be repeatedly modeled, the process of writing summaries requires well-planned scaffolding and students need a lot of time and opportunity to practice. Students need to summarize across content areas, but it’s a formidable challenge to teach students how to write and how to recognize the “best” summary when given multiple options.

So where do we start?

In this two-part series I want to share a process I believe helps students to write succinct, accurate summaries and to identify them when asked to determine the best summary from a selection of choices.

Understand why it’s such a daunting task

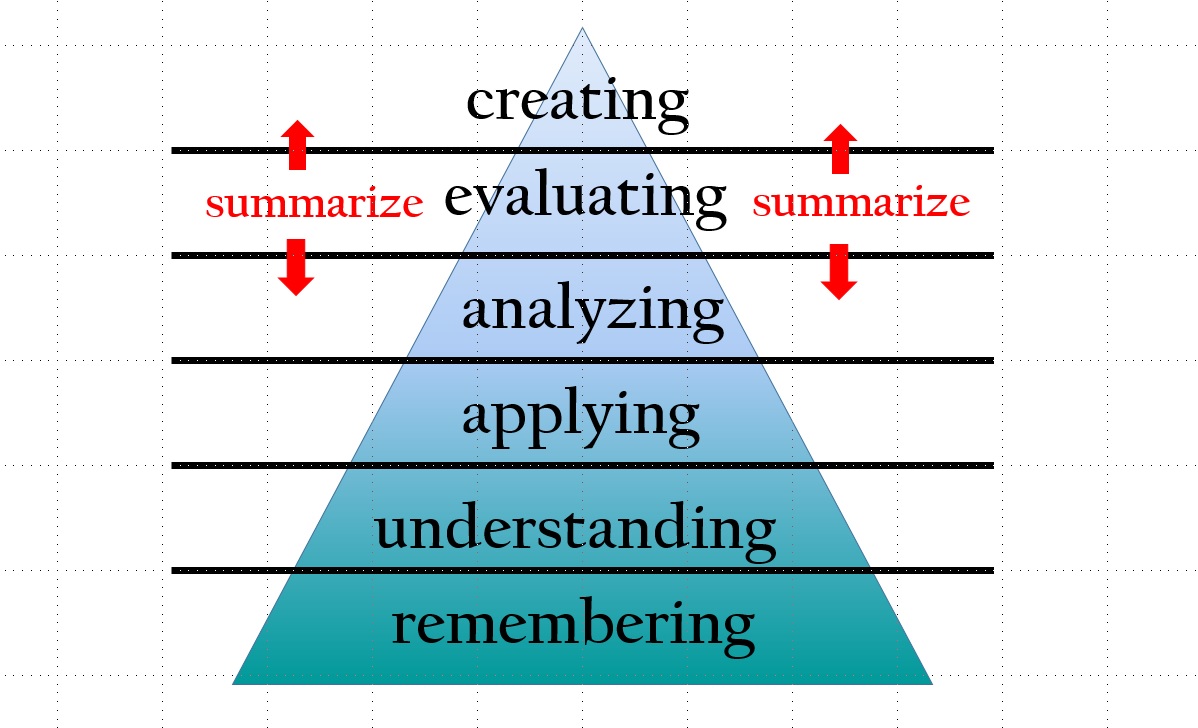

The first step is understanding why summarizing is so difficult. Students have to take a large amount of information and distill it to its most essential parts. That’s tricky for young readers. Kids have to be adept at determining what is most important in a text piece and communicate that information in a precise and concise manner. The process of correctly summarizing a selection demands that students perform at higher levels of thinking. Determining what is most important and forming ideas from the text that are written in a brief retelling requires students to analyze, evaluate and create; the top levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Provide criteria for creating and analyzing summaries

In another blog post I addressed the importance of students being provided with a repertoire of strategies for comprehending text. The same is true when equipping students to write and recognize summaries. Students need to be presented with strategy options so that when they work independently they’ll be comfortable choosing the strategy that works best for them.

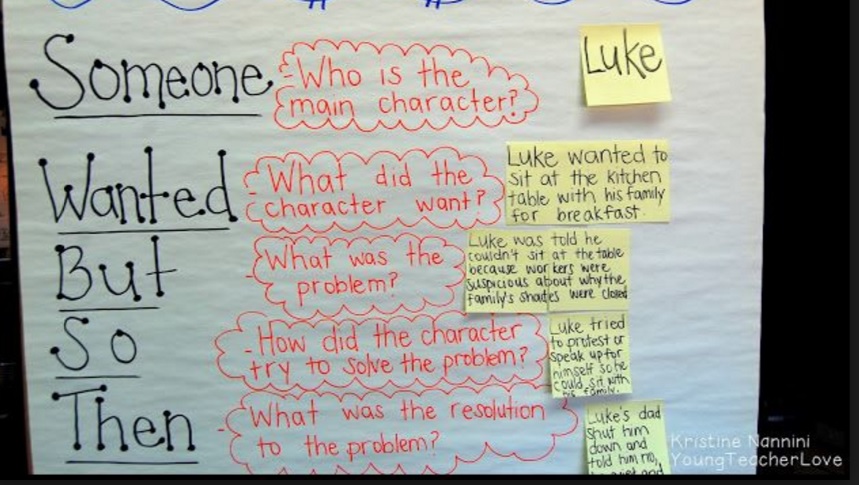

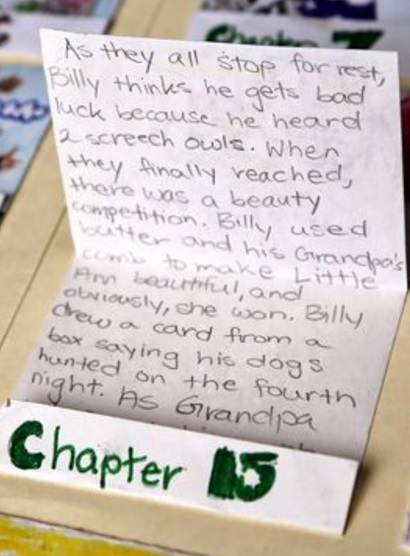

Several strategies for creating summaries come to mind when first teaching kids this skill. Using the Somebody Wanted But So Then (SWBST) helps students to state the person, what the individual wanted, the problem and then the solution.

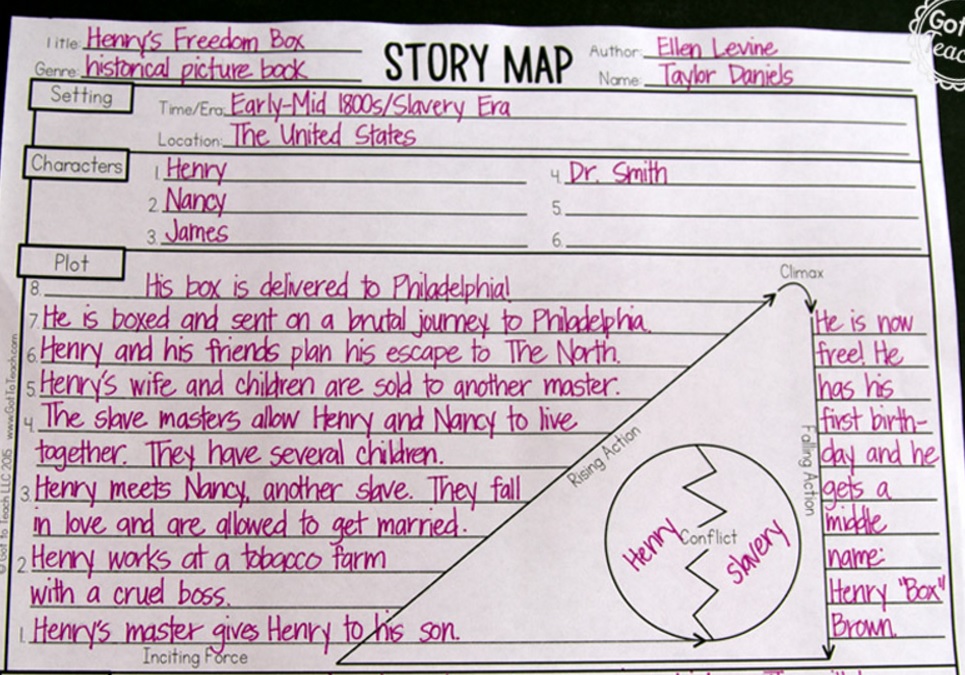

Using a plot diagram, or story map, to help students remember the important elements to include in a summary is another effective strategy. These, of course, are strategies for writing narrative summaries and there are a variety of strategies for creating nonfiction summaries as well. (Those will be addressed in Part II of this series.)

Whichever strategies are chosen must be modeled multiple times with opportunities for students to see the connection between the criteria required in the strategy and the elements included in the written summary. Once the teacher has written the summary, then together students and teacher go back and underline or highlight the specific components of the summary. This helps kids to see again and again the application of the criteria to the finished product.

Teachers can then scaffold by reading a text piece, talking through the essential pieces of the plot or nonfiction selection, and then providing students with an incomplete summary which table groups can work together to complete by adding the missing elements.

The last step in scaffolding for students as they learn to write a summary is for them to work first in groups or pairs to complete the assignment (again, using specific criteria to guide them) before moving on to creating a summary completely on their own.

In Part II, I’ll share how to create a process for helping students work together with the teacher and other peers to evaluate summaries based on specific criteria. Join me next week as we finish this two-part series on summarizing.