I’m dating myself, I know, but years ago when I read Ellin Keene’s Mosaic of Thought (1st edition) and she included Billy Collins poem, First Reader, I had a moment. A really nostalgic moment. A sobering moment. “…forgetting how to look, learning how to read.”

First Reader

I can see them standing politely on the wide pages

that I was still learning to turn

Jane in a blue jumper, Dick with the crayon brown hair,

playing with a ball or exploring the cosmos

of the backyard, unaware they are the first characters,

the boy and the girl who begin fiction.

It was always Saturday and he and she

were always pointing at something and shouting, “Look!”

Pointing at the dog, the bicycle, or at their father

as he pushed a hand mower over the lawn,

waving at aproned Mother framed in the kitchen doorway,

pointing toward the sky, pointing at each other.

They wanted us to look but we had looked already

and seen the shaded lawn, the wagon, the postman.

We had seen the dog, walked, watered and fed,

and now it was time to discover the infinite, clicking

permutations of the alphabet’s small and capital letters.

Alphabetical ourselves in the rows of classroom desks,

we were forgetting how to look, learning how to read.

–Billy Collins, Sailing Around the Room (2001)

Learning how to read. Knowing how to “look.”

Just how do kids learn to read? How do we provide space and time for young readers to look closely in an effort to make deep meaning? What should reading instruction (and mean-making) look like for emerging readers? Should we put all our efforts into feeding readers’ minds or their hearts? Or should it be both? Roskos, Christie and Richgels asked the same question a few years ago in their article The Essentials of Early Literacy Instruction. (If you’ve not read this–go now and bookmark it. This is one you don’t want to miss.)

It’s both. And I can say that not just because I have a gut feeling about it. I can state that with confidence because there is some pretty impressive research to support the assertion that reading instruction should be directed at teaching cognitive and metacognitive skills as well as connecting with young students on an affective level.

This is so critical that I’m reading research and reflecting on our practice a lot already this summer. I must know what the research says so I provide the kind of well-informed support that empowers all of our kids to learn to read. We have to be clear on what’s important, and what page upon page of research says we must do in order to create classrooms where students get the very best head and heart instruction to be proficient, self-directed readers. We know this. We know that readers must do more than simply read the words. But do we spend as much time on the meaning-making and the life-altering bits of reading?

WARNING: this is where I go off on “cute” activities versus sound instruction.

We cannot, I repeat, cannot rely on Pinterest and Teachers Pay Teachers to direct us to the type of reading instruction that results in deep-thinking, independent, empathetic, confident readers. Don’t get me wrong. There are some acceptable resources from both of those oft-visited sites. In an effort to find something quickly and easily to plan for instruction however, Pinterest and TpT allow educators to grab something eye-catching and cute. We need to be done with eye candy reading instruction. Let’s dig deep and find out what must be done in order to support emerging readers on the path to becoming highly proficient readers.

So if you’re still with me here and you didn’t exit when I stepped on Pinterest and TpT toes, here’s what I propose. Let’s look closely at sound, research-based reading instruction over the next few weeks. I’m going to be writing a six-part series on what readers need. The forthcoming blog posts will focus on:

Reading Books: Knitting Hearts Together

Phonological Awareness and Alphabetic Principle

Support for Emergent Readers and Writers

Occasionally, I hear someone outside the education community remark that teaching is not rocket science. Those who would say that are either intentionally or unintentionally led astray (doesn’t matter which) and need a little enlightenment. Teaching, and teaching reading in particular, is both a science and an art. It requires hours of preparation, deep reflection and well-thought out planning. The 187 days each school year allotted for teaching a child to read are full of drama, trauma, joy and frustration. Teaching children to read is not for the faint of heart. Nor is it for the misinformed, or the ill-equipped.

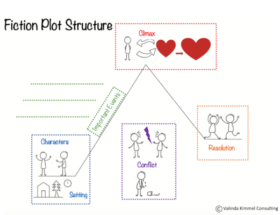

Children need to learn mainstay concepts and skills of written language from which more complex and elaborated understandings and motivations arise, such as grasp of the alphabetic principle, recognition of basic text structures, sense of genre, and a strong desire to know. They need to learn phonological awareness, alphabet letter knowledge, the functions of written language, a sense of meaning making from texts, vocabulary, rudimentary print knowledge (e.g., developmental spelling), and the sheer persistence to investigate print as a meaning-making tool. (Roskos, Christie and Richgels, 2003)

Together let’s investigate how to teach readers’ heads and hearts so they persist beyond just learning to read.

Join me here.

I couldn’t agree more…Teaching, and teaching reading in particular, is both a science and an art.

Great post.

Love the topics and so agree with you!