Today’s blog post is authored by my friend, Jill Shelby. I met Jill earlier this year at our first instructional specialist meeting. There was an instant connection. Jill’s family and mine both experienced re-entry to America after living abroad. I’m so pleased and honored that Jill shared her thoughts here about our privilege and responsibility to offer a place of solace for our students that are new to this country. You can engage in further conversations with Jill at jillshelby@hebisd.edu

As long as there is respect and acknowledgment of connections, things continue working. When that stops, we all die. –Joy Harjo

There’s a map of Africa in my office. It includes parts of the Middle East and Southern Europe. First graders have been coming in to my office for reading assessments. Several stop short with eyes of recognition. Some sheepishly and some proudly tell me, “I lived there” or “My dad is from there”, pointing to Sudan or Somalia, Congo or Nigeria, United Arab Emirates or France.

A world of connection opens up as I briefly share that I lived in Rwanda for eight years and have only been back in the United States for less than two years.

We smile, and unspoken, somehow know what we’re both not saying. My eight and six-year old did their growing up in Rwanda and are struggling in some ways with living in their passport country. As Wright Morris said, “Home is where you had your childhood.” I look at these little ones and I think they are growing up in the U.S. and this is their home. Just like my little ones consider Rwanda their home.

Today in light of the current political climate and recent national decisions, I have been reflecting on these very students–refugees and immigrants. I have been asking myself as an educator and coach of teachers,

- What can we do?

- What is our role?

- How do we step into this global moment in a way that promotes peace, mutual respect, and what we all value in this field—learning?

- How do we respond both to current immigrants and refugees and those seeking to make America their home?

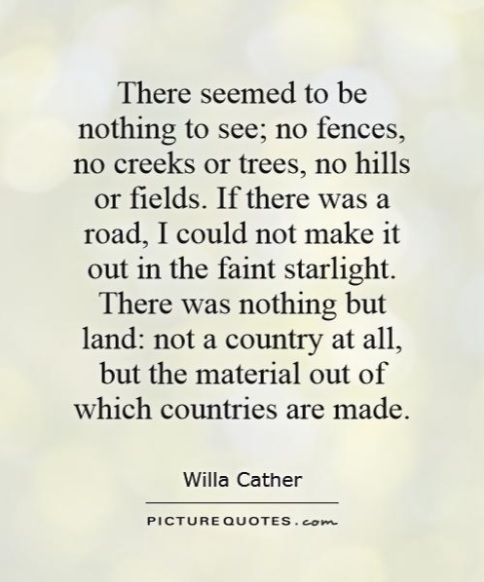

I went back and skimmed a book I had previously read, given to me by a dear friend and mentor– The Middle of Everywhere: Helping Refugees Enter the American Community by Mary Pipher.

There’s a chapter on schools. I will share both verbatim and in summary here:

Schools are the sacred ground of refugees [and immigrants], and education is their shared religion.

Before their first day of school, many children from traditional cultures have never been away from their mothers for even an hour. At school, they may feel far from home. Everything may be different—language, customs, the colors of the people, the clothes, the foods, and even the play. Developmental levels of children are not uniform either. Five-year-olds from one culture have very different skills, relationships to family, and comfort levels with strangers than do five-year-olds from another culture.

Schools are often where kids experience their first racism and learn about the socioeconomic split in our country. There is the America of children with violin lessons, hockey tickets, skiing trips, and zoo passes, and there is the America of children in small apartments whose parents work double shifts. School may be overwhelming at first, but it is school that will enable children to make it in America. School offers students the freedom to develop and to dream big. In spite of their disadvantages many non-native-born kids thrive in school. A determining factor is the quality of their family lives. Mothers and fathers who carefully select the best from both the new and old cultures have best-adjusted children. Parental involvement in education varies. In general, non-native-born parents have high expectations, but limited contact with schools. They feel that education is the job of the teachers. Parents may want to be involved, but may not understand how to be involved. Also, work schedules, transportation, and language barriers make contact with schools difficult.

Schools can be therapeutic environments. Teachers can give their students order and predictability. After the chaos and confusion of their lives, nothing is more comforting than routines. Students needs to receive the message that school is a safe place—physically and emotionally. Order, ritual, and predictability are part of this reassurance. Relationships with kind, consistent adults are deeply healing. They give children time, pats, and nonverbal reassurance that they are going to be okay. Physical affection and smiles can occur in the absence of common language. A hug has a universal meaning.

Teachers connect the dots between the world of family and of school, the old culture and America, the past and the future. They can help children understand how their worlds fit together. They teach empathy and manners, not through lectures but through countless daily encounters with moral people. They learn how to be good through stories about honesty, kindness, responsibility and courage.

After reading this and dialoguing with others, I think what we as educators can do is:

- Be good: Smile more. Reassure often. Be consistent and consistently kind.

- Be curious: Watch and listen to the students currently in our classrooms from other countries and cultures. Get to know them. Get to know their families.

- Be open: How can we allow these children to shape and change us for the better? We need to hear their stories; they are far more interesting and hopeful than many of the stories we do hear.

We hear the soundbites on the news and read the links to Facebook articles, but every story has a face now. Nothing abstract and faraway anymore. How do we allow our students to grow us, enlarge our perspective, broaden our definitions, expand our capacity to love and include “the other”, to come to the realization that there was no “other” all along, there always was just “us”?

We are all just walking each other home. –Ram Dass

—Jill Shelby

I am referencing this post on my Masters course- Multicultural literature- Your experience is inspiring and it is so much a part of you. I am lucky to know you and call you a friend.

Thank you, Valinda, for letting us hear her voice.