This post was published earlier this year and the response was overwhelming so I’d like to repost. If you’re like the teachers on our campus, the middle of year (MOY) early reading scores are back in. We’ve also been looking at our upper elementary grades at individual students’ needs and this blog post by Russ is the perfect reminder for intervention that makes a difference.

I’m so honored that today’s guest blogger is Russ Walsh. I found the blog Russ writes, Russ on Reading and became in instant fan. Russ has a career in education that spans four decades. He has served as a teacher, literacy specialist, curriculum supervisor and college instructor. Currently, Russ is the Coordinator of College Reading at Rider University in Lawrenceville, NJ. He has authored several books; his most recent is published by Garn Press, A Parent’s Guide to Public Education in the 21st Century: Navigating Education Reform to Get the Best Education for My Child. You can follow Russ on Twitter @ruswalsh and on Facebook

Every classroom teacher faces the dilemma at some time during the year. Some readers, despite the teacher’s best efforts through direct instruction, small group guided reading, and independent reading, reach a plateau and do not seem to advance to more complex texts for weeks at a time.

What to do?

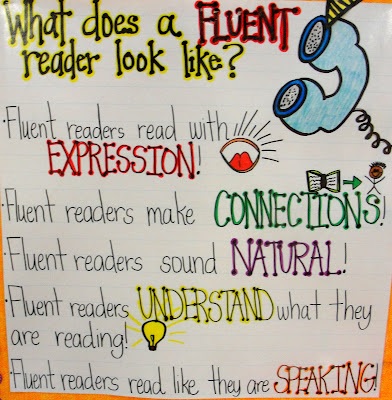

One possible intervention that holds much promise for moving students forward to more sophisticated text is fluency instruction. Fluency instruction has been called the “bridge” between decoding and comprehension and sometimes it is exactly the bridge that some readers need to move forward.

What is fluency?

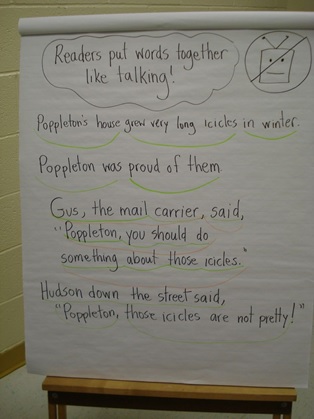

Fluency is the smooth, accurate, expressive processing of print. As I tell my students, “Fluent reading is reading that sounds like talking.”

Why is fluency important?

Reading fluently allows the reader to gather meaning while reading. This gathering of meaning is the key, not only to comprehending text, but also to decoding new words. Decoding is best seen as a meaning driven process that involves the meaning of the word (What word would make sense?), the structure of the sentence (What word would sound right here?) and the visual representation of the word (What word would look right?). Fluency instruction helps the reader push through the text gathering meaning and quickly identifying words.

How do I teach for fluency?

Fluency may be taught through direct instruction with the whole class or small groups, through prompting as children are reading, or through oral reading activities like readers theater.

Direct Instruction in Fluency

Tim Rasinski, professor at Kent State University in Ohio, has studied fluency instruction for years. One of the things he has discovered is that direct instruction in fluency has transferability. That is, when we provide direct fluency instruction on one reading passage, students seem to transfer that knowledge to subsequent reading. Any short, interesting text will do for fluency instruction.

In my book, Snack Attack and Other Poems for Teaching Fluency to Beginning Readers, I suggest the following instructional procedure for developing fluency through poems. In preparing for the lesson, I put the poem on chart paper or display on a Smartboard. I also make a copy f the poem for each student.

- Pre-reading Activities: Before reading the poem, activate background knowledge and interest through discussion. Using the title, illustration or an appropriate question as a stimulus, have the children make predictions about what they will read in the poem.

- Teacher Modeling: Read the poem aloud to the class at least once. Emphasize meaning. Read expressively. As you read, point to the words on the chart or screen in a smooth, left to right motion. Children need to hear the poem read fluently and expressively so that they can learn what fluent reading sounds like.

- Comprehension Instruction: After listening to your oral reading of the poem, have the children check their original predictions about the poem’s content. In a guided discussion help students to retell what happened in the poem. Discuss difficult vocabulary and figurative language. An understanding of the meaning of the poem will support students in developing their reading fluency.

- Echo Reading: Read aloud one line of the poem and have the children echo back what has been read. Read the next line, have the children echo again and so on throughout the poem. Be sure to point to each line and keep students focusing on the text. Some students may not look at the text during echo reading, relying instead on listening memory. Guide them to keep their eyes on the words as they echo.

- Choral Reading: Lead a re-reading of the poem. Invite all students to join in the re-reading. Weaker readers can rely on classmates to help them over the difficult passages or may choose to be silent or listen. Again, remember to point to the words as you and the children read them together.

- Paired Reading: Children are each given a copy of the poem and are asked to choose a partner. Alternatively, the teacher may assign partners. Have children find a comfortable place to read and then take turns reading the poem to each other. The listening partner is asked to play the role of helper, listening and following along closely to provide help if the reader needs it. Partners are encouraged to keep reading to each other until each can read the poem fluently.

- Teacher Conference: When children feel they have mastered the poem, they request a teacher conference. During the conference, the child reads the passage aloud, while the teacher keeps a record of general fluency, miscues and decoding strategies employed. The teacher provides specific feedback to the student on their fluency and use of strategies.

Choral and echo reading may be repeated several times until the teacher feels that most students will be able to combine memory, sight vocabulary, and decoding strategies to read the poem independently. After a few choral readings, the teacher can stop reading and have the children read chorally without the teacher’s guiding voice.

Vary choral reading as the poem warrants. Have different small groups of students alternate verses or lines or have students take the parts of speaking characters in the poem. Have pairs of students read parts of the poem or have the boys read one time and the girls another. Variety in choral reading will help keep interest and attention high.

Prompting at the Point of Difficulty

During guided reading or independent reading, when you are listening to students read orally from the text, prompts can help students attend to the importance of fluency. Favorite prompts for this include the following.

- Read that again and make it sound like talking.

- Read that again and be sure to pay attention to the punctuation.

- Read that again like you were telling me the story.

- Listen to me read this part and then see if you can read it like I did.

For students who struggle with this, it can be a good idea to focus on small chunks first, for example just reading the “she said” chunk together to build the idea that words are grouped together.

Oral Reading Activities

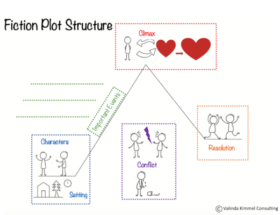

Oral reading activities are wonderful for developing fluency because they encourage students to read a text several times for “rehearsal.” The research evidence is clear that repeated reading helps students improve fluency, decoding abilities and comprehension. Scripts for readers theater are readily available commercially, but I prefer to have the students do their own adaptations of fairy tales and folktales for a readers theater performance. Books like The Three Billy Goats Gruff and Henny Penny lend themselves well to readers theater.

A less time intensive alternative to readers theater is radio reading. In this activity, children rehearse a story and then gather around a (pretend) microphone, bringing the story to life with only their voices. You can learn more about radio reading here.

If you find some of your readers are “stuck” on a particular level of reading, try doubling down on fluency instruction to see if you can give them a kick start to more complex reading.

–Russ Walsh

Such great suggestions! I often struggle between deciding whether or not to focus on decoding or fluency. This is such a good idea, to use the poem to illustrate the meaning of fluency and the different approaches to get it! Thanks!

I found Russ’s suggestions to be incredibly helpful, too. So glad you found his post inspiring!